Customer relationship management (CRM) is the biggest, fastest growing software market in the world. $40B is spent on CRMs annually, and almost all companies have one. But for those of us that don’t directly use a CRM… what’s the big deal?

A CRM is the source-of-truth for all customer data and interactions. Need to know what features your salesperson promised, and when? How much revenue you have from each customer? Or which salesperson sold the most in the past year? Check the CRM. Your CRM is the key to understanding the business side of your company. You can learn about how Retool uses CRM in this post.

Salesforce is the most popular CRM in the industry. It’s worth $120B, owns 20% of the CRM market, and is used by 83% of Fortune 500s. The company employs over 30,000 people, and Salesforce Tower is the tallest skyscraper in the San Francisco skyline.

An entire economy is built around Salesforce. For every dollar that Salesforce makes, its ecosystem generates $4. Millions of developers build apps for Salesforce’s platform, and Salesforce development is itself a lucrative niche within software engineering. The IDC estimates that by 2022, Salesforce will have created 3.3 million new jobs, as well as $800B in new business revenues.

Today, enterprise software has a reputation for being clunky, boring, and slow. But Salesforce, the archetype of enterprise software, actually pioneered much of what we now take for granted in tech, including selling software as a service (=> SaaS), and hosting software in the cloud (=> AWS), all while creating a massively valuable company.

To understand how Salesforce took over the world, it helps to understand how sales worked, before Salesforce.

Back in the day, sales used to be a completely manual process. Companies stored contacts on physical index cards (a “rolodex”), who they targeted by direct mail or telemarketing. With the advent of personal computing in the 1980s,“ contact management services” started cropping up, digitizing the salesperson’s rolodex. “Database marketing” became the next hot thing, and companies started storing customers and leads electronically. This let them segment their leads and target them with custom marketing messages.

In the 1990s, the market moved towards a single idea: a unified store of all customer data with features to automate the sales process, including contact management, task tracking, and reporting. Different companies gave it different names — SFA (Sales Force Automation), CIS (Customer Interaction Software), ECM (Enterprise Customer Management), and a host of other TLAs (three-letter acronyms).

One eventually stuck — CRM (Customer-Relationship Management).

Why use a CRM?

Storing sales details is a basic requirement of running any business. You interact with various entities throughout your day — individual contacts inside existing companies (Contacts in Salesforce lingo), individual contacts who might become customers (Leads), companies themselves (Accounts), deals with a company (Opportunities), etc. And every time you interact with them, you’ll be either writing notes down, or referencing previous notes. For example, when a lead comes in and is interested in purchasing, you’ll want context: have you called them before? What’s their use case? When should you follow up on them?

When you’re just starting out, a spreadsheet works well. You have multiple tables (Contacts, Companies, Opportunities, Leads etc.). Sure, manually checking before you enter each row (for duplicates, validating inputs, validating foreign keys, etc.) takes effort, but you don’t have that many customers anyways.

But as you get more customers, you’ll want a variety of features (various validations, triggers on creating rows, de-duplication logic, etc.), which spreadsheets don’t always offer. That’s where a CRM comes in.

A CRM is the single source of truth for all your business-critical data. It’s where you track lead data — how much they’re worth, how far along they are, and how likely they are to close. It connects with your email (and sometimes even your phone) to automatically sync interactions with them. Unlike a spreadsheet, it’s designed to automate data entry, and minimize errors.

Once all your data is in the CRM, you can run reports on it. For example, you could group deals by salesperson responsible (find your top performing salesperson), by industry + company size (find your sweet spot: CPG companies between 100 - 1000 employees), or whatever else. Salesforce, for example, even allows you to write SOQL (“Salesforce Object Query Language”, which is very similar to SQL) to run reports. Oh, the power!

So far, you might think CRMs are valuable, but boring. Just a CRUD app, plus some automated email + call logging, right? Well… most CRMs are just that — CRUD apps with automation.

But not Salesforce.

Enter Salesforce

Every business is unique. Different domains have different entities — you might need to track a “faculty” within a “university” for selling to academia. And different organizations have different processes — you might need a specific “lead qualification” view if your team has specialized Sales Development reps. How do CRMs handle these varying needs?

And that’s just the model. Maybe you need custom views and controllers as well! Many SaaS apps are worse than internally-built ones, often because you can’t customize the UI. For example, we use Intercom, and it’s oftentimes infuriating that simple, mundane tasks (e.g. email this lead now) isn’t possible. It would be great if we could just add a button into the view… but of course, we can’t edit it, since it’s a SaaS product that we bought, and have no control over! (This is related to Patrick Collison’s question on programming end-user applications.)

Some CRMs force all companies into a one-size-fits-all setup. Salesforce is so successful, in large part, because it doesn’t. Its killer feature, instead, is its flexibility.

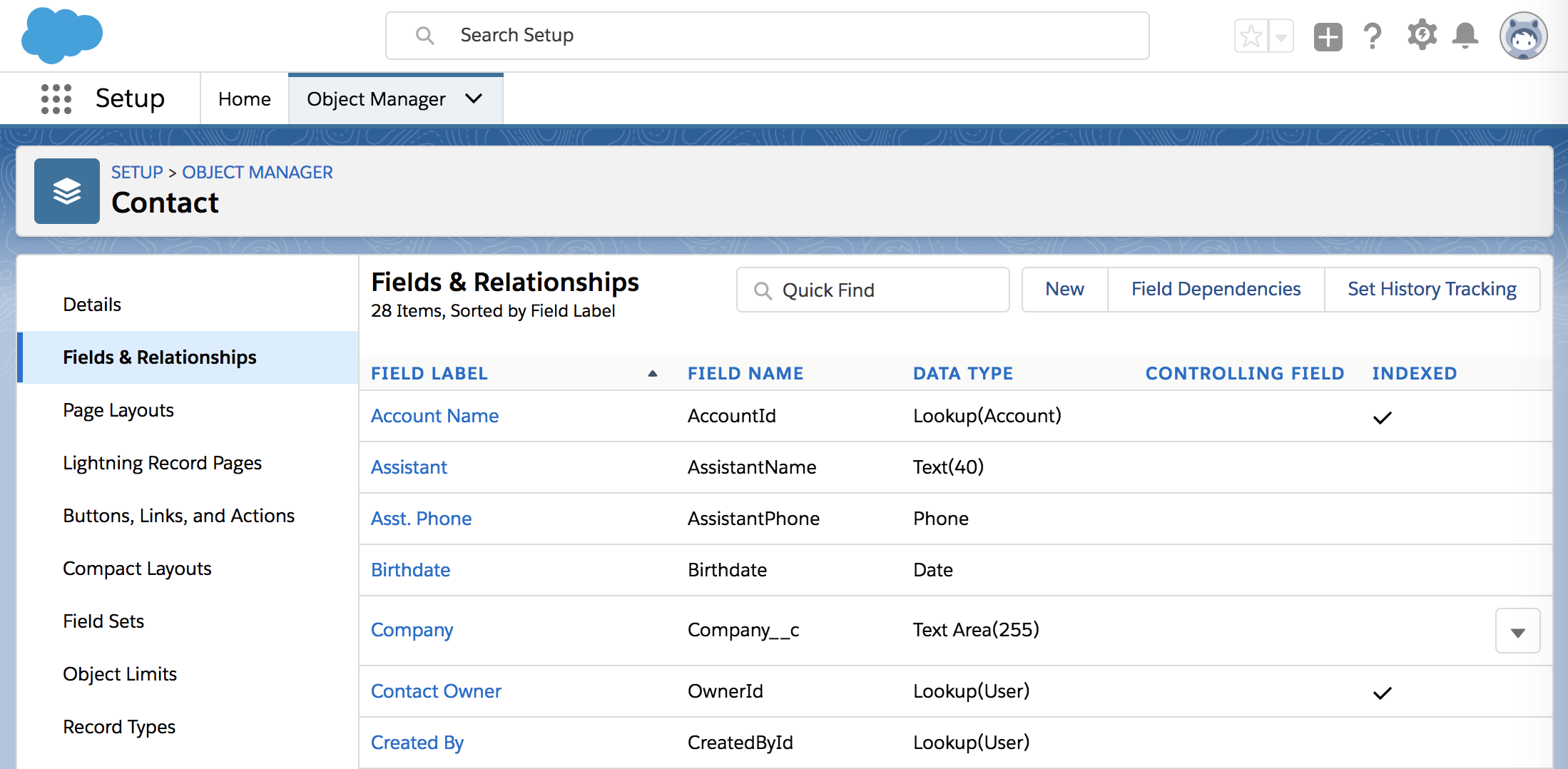

Like a database, Salesforce lets you create new tables with custom columns and relationships, complete with data types and constraints. For selling to academia, you can create new “university” and “faculty” objects that can be linked to each other and attached to each “lead” object. Unlike a database, Salesforce lets you do this without writing any code.

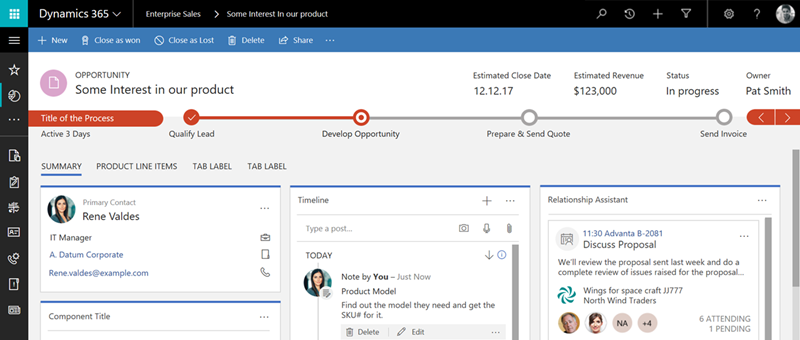

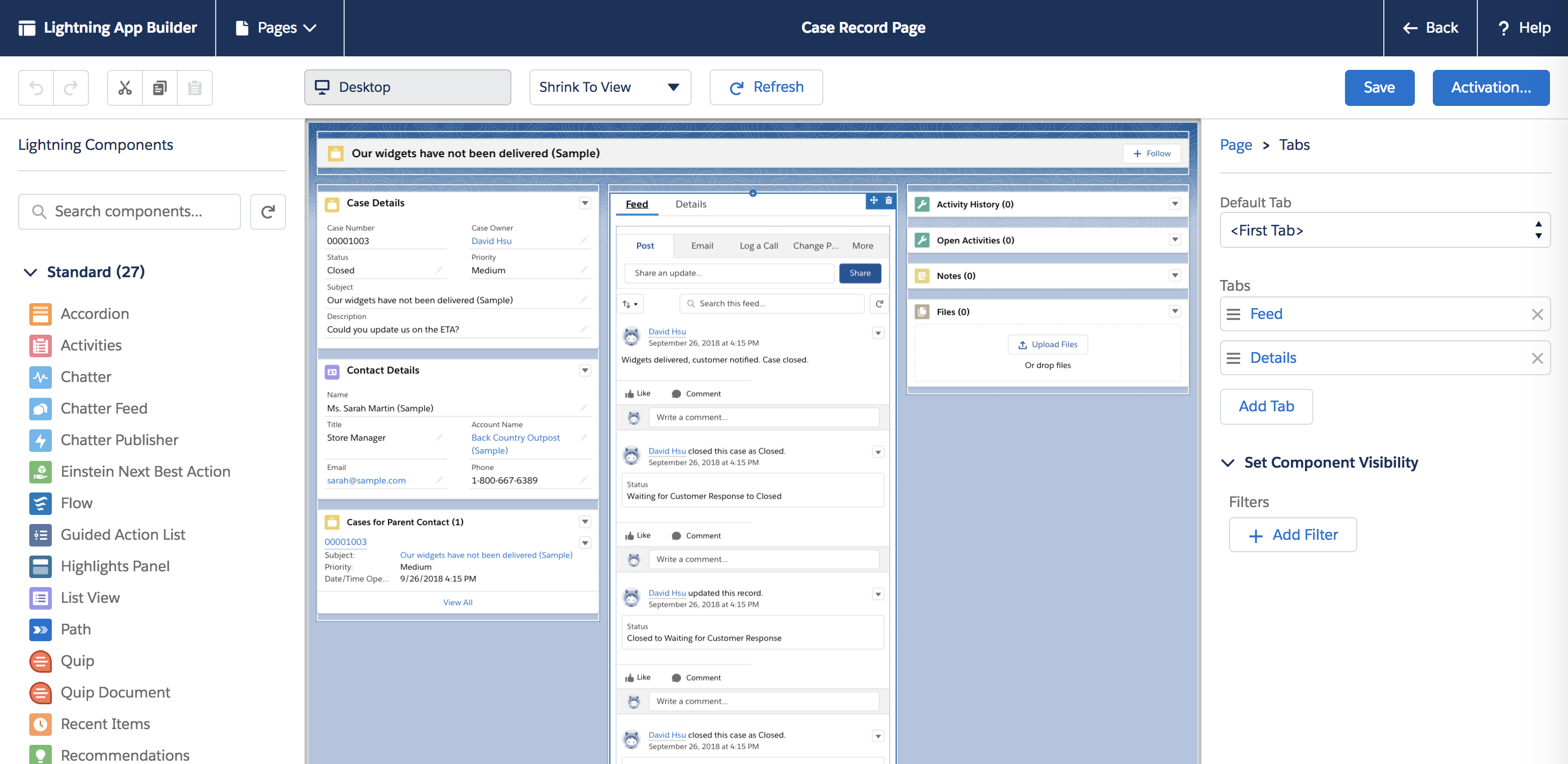

Like a frontend framework, Salesforce lets you can create new views with custom layouts and UIs. For a lead qualification process, you can create a dashboard showing only unqualified leads and the information needed to approve/reject them. Unlike a frontend framework, Salesforce lets you do this without writing any code.

And like AWS Lambda, you can write arbitrary code and trigger it by POSTing to the Salesforce API. Unlike Lambda, though, this code can be triggered automatically by database events — after a Lead is edited, or an Opportunity is created.

With Salesforce’s custom data models and interfaces, every company’s setup is unique. Viewed that way, Salesforce isn’t just a CRM — it’s a platform for building CRM-like apps, but with sane defaults.

Salesforce’s point-and-click database editor and drag-and-drop UI builder alone make it much more than a CRM. But when you bolt on other apps and 3rd-party APIs, it gets close to programming without code: a new way to build software.

Custom data models and UIs makes the vanilla Salesforce platform configurable enough (by non-engineers!) to meet most business needs. AppExchange then enables a host of new functionality via “plug-and-play” apps, allowing for even more custom setups. And finally Apex fills any final gaps, letting developers write custom code for truly bespoke features.

How did Salesforce get here?

A brief history of Salesforce

Sometime in the late 90s, a seasoned enterprise software executive was sitting inside a hut in Hawaii, thinking about the future. (This was parodied in Episode 3 of Silicon Valley).

For 10 years he’d lived Oracle’s business; one of multimillion-dollar up-front costs, multi-year-long on-premise implementations, and constant maintenance overheads. He’d also seen the trend in consumer software towards simplicity and ease-of-use, led by online bookstore Amazon.com. He wondered how to do the same to enterprise software.

This executive was Marc Benioff. Returning from Hawaii, he set out to simplify enterprise software with a new company called Salesforce.

Salesforce’s first innovation wasn’t its features, but its business model. Benioff wanted software to be a utility, like electricity. So he gave Salesforce simple subscription pricing that scaled according to usage. In 1999, it was $50/user per month. Software-as-a-service (SaaS) was born.

Software, at the time, was synonymous with complexity and cost. With its counter-culture philosophy, Salesforce needed to differentiate itself. They did so, and not subtly — the company’s first marketing slogan was “No Software”, and, conveniently, their phone number became 1-800-NO-SOFTWARE. Most of the company were against this — negative advertising is generally a bad idea. But for Salesforce, it worked.

For a company that wanted to end software, Salesforce sure contributed a lot to its progress. 6 years in, they launched the first ever “app store”, creating a brand new method of software distribution. This pre-dated even Apple’s, but not by coincidence —

Steve Jobs gave Benioff his first programming job (writing assembly) back in 1984. Benioff describes him as one of the greatest mentors he’s ever had. During one of their meetings in the early 2000s, Jobs gave a piece of advice that changed Salesforce’s trajectory:

“You’ve got to build an application economy.”

“What’s an application economy?”, Benioff asked.

“Marc, you’re gonna figure it out.”

Salesforce did figure out. In 2005, they launched AppExchange, an online marketplace letting anyone develop and distribute apps that connect with Salesforce. Because those apps live inside Salesforce and can read / write Salesforce data, they’re extremely powerful. For example, the Mailchimp app lets you subscribe people inside Salesforce directly to Mailchimp. But it also includes a front-end that allows you to see a lead’s interactions with previously sent emails (e.g. Alice viewed your marketing email 5 times, and clicked on the Foo feature three times).

Some AppExchange apps integrate into Salesforce’s web app, while others are standalone with a backend integration. Billions are now spent annually on thousands of AppExchange apps, and entire companies have been built on it — FinancialForce.com, for example, lets you build an enterprise resource planning system (ERP) in Salesforce, employs over 750 people and has raised $200M since it was founded in 2009, for example.

Benioff originally planned to call it “App Store” — he even registered the ‘appstore.com’ domain — but market research suggested that “exchange” was the better metaphor. The domain didn’t go to waste, though — Benioff gifted it to Jobs at the launch of the iOS App Store, along with the “App Store” trademark. It continues to be a major part of Apple’s brand.

The last time I saw Steve Jobs he asked this photo to be taken. I did not realize how important it would be to me. pic.twitter.com/FnFbzNG6BC

— Marc Benioff (@Benioff) 11 September 2013

In the years following AppExchange, Salesforce launched a set of products more faithful to their “no software” goal.

The first was Apex, the Lambda-like service that allowed Salesforce users to write arbitrary code. Apex apps, once installed via AppExchange, could access the user’s database and Salesforce’s client-server interfaces, so made almost any custom functionality possible.

The second was Visualforce, a component-based UI framework that made it easy to build custom interfaces for Salesforce. Its simple markup let developers build UIs that were consistent with the rest of the Salesforce app, and that could easily talk to Salesforce’s servers.

This Visualforce code would generate a form with a dropdown list of objects:

<apex:page controller="objectList" >

<apex:form >

<apex:SelectList value="{!val}" size="1">

<apex:selectOptions value="{!Name}"></apex:selectOptions>

</apex:SelectList>

</apex:form>

</apex:page>

And this Apex controller code would fetch the list of objects from the organization’s schema:

public class objectList{

public String val {get;set;}

public List<SelectOption> getName()

{

List<Schema.SObjectType> gd = Schema.getGlobalDescribe().Values();

List<SelectOption> options = new List<SelectOption>();

for(Schema.SObjectType f : gd)

{

options.add(new SelectOption(f.getDescribe().getLabel(),f.getDescribe().getLabel()));

}

return options;

}

}

In 2008, these were consolidated into Force.com — a platform for developers to build and run apps without worrying about infrastructure. It was the first platform-as-a-service (PaaS).

Force.com opened up Salesforce’s services and architecture to developers, who flocked to build custom Salesforce apps on it. It wasn’t just faster to develop on — Force.com also made distribution significantly easier. Apps on the platform benefitted from Salesforce’s own security, which IT departments already approved of, so Force.com apps were easier to sell to enterprises.

Salesforce continues to launch new products every year to enhance its offering. $3.6B of acquisitions were turned into the Salesforce Marketing Cloud in 2012, a suite of tools for digital marketing automation. Einstein Analytics was launched in 2016, adding a layer of “AI-powered” analytics across the entire Salesforce stack. And in 2018, the company entered a new vertical with a CRM specifically for healthcare — Salesforce Health Cloud.

When Salesforce called for “the end of software”, Salesforce was referring to the legacy model of enterprise software: boxed, bloated, and sold via salespeople. Today, they’ve succeeded in changing how software is built, bought, and deployed across enterprises. Technology like Retool is doing much the same thing for internal apps and operations software.